22 Jun 2009

Would you know if you’re a good listener?

I was at a conference this weekend, and met two people who have been on my mind.

I was at a conference this weekend, and met two people who have been on my mind.

One of them, LucÃa, was a gracious and skilled listener. She really took in what I was saying, was curious about the ideas, was really present. We had a real, two-way conversation.

And the other, Marc, was a passionate talker. He’s the sort of person you might find on one of those CNN debate shows, hurling one-liners across the table. That interaction was interesting, but mostly one-way, with me as the audience.

But here’s the strange thing: LucÃa, whom I thought was a pretty good listener, said “I’m not a good listener—I need to take your workshop.â€

Whereas, Marc, who demonstrated little interest in listening, said, among other things, “Listening? Oh I already do that.â€

And this was by no means an isolated experience. What I’m finding is that the people who say “I’m not a good listener” generally demonstrate strong listening skills in that very conversation.

I don’t know if it’s just modesty that leads them to claim that they aren’t good listeners, or if they genuinely see opportunities to improve. My hunch is that it’s the latter—above average listeners have the perspective to see that being an even better listener is possible and desirable.

And on the flipside, I often find that those who proclaim to be great listeners tell me that they have no need to improve–all the while demonstrating poor listening skills in the conversation. It’s like the activity of listening just doesn’t hold much value for them—but they still consider themselves good at it.

Where that leaves me is making a conscious decision to focus my efforts on working with those who naturally see the value of listening, connection, and relationships. Working with the strength in the community, if you will.

Several of my good friends have been going through challenging times, which means I’ve been doing a lot of Supportive Listening lately. And in my listening I’ve started to take a much more active stance towards the moments of silence that invariably happen.

Several of my good friends have been going through challenging times, which means I’ve been doing a lot of Supportive Listening lately. And in my listening I’ve started to take a much more active stance towards the moments of silence that invariably happen.

When I tell people that I teach listening, they are often surprised. Some people ask “Can that be taught?†I like to reply “I sure hope so,†with a smile.

When I tell people that I teach listening, they are often surprised. Some people ask “Can that be taught?†I like to reply “I sure hope so,†with a smile. True emotional connection is one of the key ingredients of good listening.

True emotional connection is one of the key ingredients of good listening. I sat down for dinner with “A” last night when she announced “I’m always the one talking — now I’m going to listen for you. What’s on your mind?” Now I’m certainly not one to turn down an offer for listening, and so I took a deep breath and started to talk.

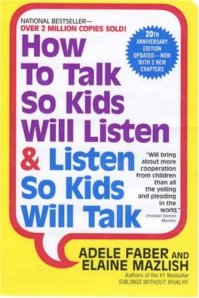

I sat down for dinner with “A” last night when she announced “I’m always the one talking — now I’m going to listen for you. What’s on your mind?” Now I’m certainly not one to turn down an offer for listening, and so I took a deep breath and started to talk. Over the past several months I have been reviewing several popular books on listening. And in the course of my reading, I have come across a wonderful book called “

Over the past several months I have been reviewing several popular books on listening. And in the course of my reading, I have come across a wonderful book called “ Over the past several months I’ve read several books on listening and have discovered a very interesting spectrum on which most books can be placed. It has to do with “extra time.” Let me explain.

Over the past several months I’ve read several books on listening and have discovered a very interesting spectrum on which most books can be placed. It has to do with “extra time.” Let me explain. Last Wednesday I was at the checkout counter at the Key Market across the street. I had bought some fruit—a few bananas, a few apples—when I realized I’d forgotten something.

Last Wednesday I was at the checkout counter at the Key Market across the street. I had bought some fruit—a few bananas, a few apples—when I realized I’d forgotten something.